- Home

- Judith Ortiz Cofer

Call Me Maria

Call Me Maria Read online

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Call Me María

Like the First Flower

Letter to Mami

Scenes from My Island Past

Part One: The Beginning of María Alegre/María Triste

Part Two: A Memory of María Alegre

Part Three: Flowering

Where I Am Now: The Tides, the Treasure, and the Trash

Here Comes Barrioman

Spanglish for You and Maybe for Me

Spanish Class, a Lesson in El Amor

Letter to Mami

Letter to María

The Papi-lindo, Fifth Floor

More Than You Know ¿Sabes?

The King of the Barrio

El Super-Hombre

Letter to María

What My Father Likes to Eat

Picture of Whoopee

Doña Segura, Costurera, Third Floor

Bombay, San Juan, and Katmandu

Golden English: Lessons One and Two and Two-and-a-Half

An American Dream

The Power of the Papi-lindo

Exciting English: I Am a Poet! She Exclaimed

Letter to Mami, Not Sent

American Beauty

Crime in the Barrio

Love in America

Life Sciences: The Poem As Seen Under the Microscope

English Declaration: I Am the Subject of a Sentence

After School, I Hear Whoopee

“Silent Night” in Spanish and Two Glamour Shots of My Island Grandmother

Math Class: Sharing the Pie

Abuela’s Winter Visit

La Abuela’s Island Lament: A One-Act Play

Who Are You Today, María?

Translating Abuela: I Know Who I Am

Translating Abuela’s Journal: The Ice Age

Translating Abuela’s Journal: After I Take Her to the Museum and the Theater

Translating Abuela’s Journal: The Final Entry

English: I Am the Simple Subject

My Papi-Azul and Me, the Brown Iguana

Rent Party

There Go the Barrio Women

My Mother, The Rain. El Fin

My Father Changing Colors

Papi-Azul Sings “Así son las mujeres”

Seeing Red: Así son los hombres

Confessions of a Non-Native Speaker

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available

Copyright

La Poesía

Y fue a esa edad … llegó la poesía

a buscarme. No sé, no sé de dónde

salió, de invierno o río.

— Pablo Neruda

Poetry

And it was at that age … poetry showed up, and it was looking for me. I do not know, I do not know where it came from, if it came from winter or the river.

— Pablo Neruda

It is a warm day, and even in this barrio

the autumn sun feels like a kiss, un besito,

on my head. Today I feel

like an iguana seeking a warm rock

in the sun. I am sitting

on the top step of the cement stairwell

leading into our basement apartment

in a city just waking

from a deep and dark winter sleep.

The sun has warmed the concrete,

rays falling on me like a warm shower.

It is a beautiful day

even in this barrio, and today

I am almost not unhappy.

I am a different María,

no longer the María Alegre

who was born on a tropical island,

and who lived with two parents

in a house near the sea

until a few months ago,

nor like the María Triste, the lonely

barrio girl of my new American life.

I am fifteen years old.

Call me María.

Sometimes,

when I feel like a bird

soaring above all that is ugly or sad,

I am María Alegre.

Other times,

when I am like a small,

underground creature,

when I feel like I will never

see the sun again,

I am María Triste.

My mother used to call me

her paloma, her dove,

when I was alegre,

and her ratoncita,

her little mouse,

on the days when I was triste.

Today I am neither.

You can just call me María.

There is one window at sidewalk level

from where I can see people’s legs up to their knees.

It is where I have my desk, even though

it is supposed to be the living room.

Since my mother has not joined us yet,

I am the decision maker when it comes to our home,

the furniture, the meals we eat, even the household budget.

I keep our place in twilight when Papi is away.

I like its cavelike atmosphere. I feel safe

from the crazy street. From my underground

home I will watch the world go by until

I am ready to surface, una flor en la primavera.

I know that spring will come someday even to this barrio.

When it does

I will break through the concrete and reach for the sun

like the first flower of spring.

Querida Mami,

I keep hoping to get a letter from you soon. I know you are busy with your new school year, but I am so lonely here.

I read all the time. My English is getting better every day. I make lists of words that I like and I play the tapes of English lessons that you made for me. All day I talk to the walls. “How are you today?” “I am fine, thank you. How are you?”

My new school looks like a prison. It has a wall around it and bars on the windows. I like some of my teachers. I have a few friends. I miss the ocean, the sun, Spanish in my ears all day.

I know you understand that I need to be here with Papi because he needs me more than you do and because of the promise he made us that I could live with him until I finish high school and am accepted to a good American university. I think he misses you, Mami. I know he does not write letters, but he always asks me what you say in your letters to me.

I miss you too, Mami. I wish I were looking for shells on the beach. It seems we could always find something beautiful the sea had washed up, like a little gift for us. There is very little beauty in this barrio. I feel like I am doing penance. Do you remember when I was preparing for my First Communion and you used to drill me in catechism? I learned then that sometimes you have to pay now for a reward later.

Do not forget me.

Con mucho cariño, tu hija,

María

The Beginning of María Alegre/María Triste

I am usually María Alegre.

I like to play tricks on Mami. We will talk in English in the morning and Spanish in the afternoon. She is a teacher of English and a storyteller. She can tell stories in both languages.

We live in a cabaña, a little cement cabin, one of many that are rented out to people who want to spend time on the beach. We get ours free because Papi is the manager. He gets up before the sun is out to run a giant rake pulled by a tractor over the sand. People always leave trash at night. Sometimes Mami and I get up with him and do a treasure hunt.

One day I run into the sunny kitchen. I am wearing my mambo costume, I have painted my face like a clown’s, lots of red lipstick and thick blue eye shadow. I climb up on a chair; Mami’s red Mexican skirt is draggi

ng on the floor. I am six years old.

“Can we dance today, Mami?” She gulps down some of her milk, leaving a red lip-mark on the glass. Mami sighs, both amused and exasperated. Mami places the bowl of steaming oatmeal on the table in front of me and pours herself a cup of café con leche.

“I want some.” I pretend to reach Mami’s cup, but she is faster. Some coffee spills on the yellow vinyl tablecloth anyway. Mami does not say anything.

She usually laughs at my tricks. But she has been very thoughtful and quiet these past few days since she got the telegram from Papi, who has been in New York visiting relatives. Tomorrow, she will take a bus to pick him up at the airport in San Juan. While they are in San Juan, they will visit Papi’s doctor. Papi has been sick, and the doctor told him he needed to take time away from his job.

I am to stay with Mami’s mother, Abuela, the three or four days that they will be away. They will bring home a new car, she has added. My grandmother said I was the happiest baby she had ever known and started calling me alegre, which means “happy” in Spanish. For a long time I thought it meant “crazy.” Then Mami started calling me her María Alegre, and I knew what she meant. I like to make Mami smile and laugh. I want her and Papi to be happy. So I have to be María Alegre.

“Can we dance today, Mami?” Music makes Mami alegre.

“Yes, María Alegre. After we have digested our breakfast I will dance with you.” I know she does not feel like dancing. I have seen her sad look when she gets off the telephone with Papi.

“Can we play a Celia Cruz album?” I keep trying to cheer her up. She loves dancing to Celia Cruz’s songs. She says that Celia Cruz is seriously alegre.

“Why don’t you go play your Disney records, María Alegre?”

“I want to learn how to do the mambo today.”

Mami and I clear the table. I tip the bowl of avena and lick the bottom. Oatmeal with lots of cinnamon is my favorite. I sprinkle some more cinnamon on my spoon and lick that too. Mami does not even seem to notice. Today, she does not think anything I do is funny. I help her wash the dishes. We hear a skip in the song that is playing, and I see the gooseflesh on my mother’s arms. She smiles sadly at me. She loves those old songs.

I ask Mami to tell me more about Papi’s tristeza.

“Hija, you have noticed changes in your father, no?” Mami speaks to me in English, saying the words slowly so that I can follow her. She knows that I will answer her in Spanish because even though I know English, I feel more comfortable speaking in Spanish. She and Papi talk to each other in very fast Spanish. But she thinks I should know English in case we all move to the United States. My father is always talking about moving to the city where he lived as a teenager before his parents moved back permanently to the Island. He has always felt out of step with the island Puerto Ricans, although he has been here so many years and married an island girl, an island girl who wants to stay on the Island. They fell in love because she spoke English very well; it was her best subject in school.

“Your papi is sad.” My father used to be the most alegre one in our family. But ever since Mami told him that she was going to teach full-time at the Catholic school, he has become very quiet. “Yes, hija. He is sad, very sad. The doctor calls it depression. It is a tristeza that is very serious.”

“Will he get better?”

“I do not know, niña. Tomorrow I will go to the hospital with him. He will have tests done. Then I will meet his doctors and try to learn what I can do to help him.”

“Shouldn’t I go with you, Mami?”

“You forget, María,” she pats my hand with her soapy hand, “you have to go to school.”

“Will he get another job?” Papi had said to us that he did not want to sweep the beach anymore.

“Not right away.”

“Will you keep your job?” Mami was an English teacher at my school.

“Yes, the children and the sisters depend on me.” This made her smile a little. She really loved teaching, and all my friends loved her.

The tiny smile on my mother’s lips encouraged me to try to make her laugh. I turned my alegre volume to max.

“Let’s mambo, Mami!” I grab the set of maracas from the wall where we keep them hanging on a nail “in case of an emergency party,” my father liked to say. Mami finally laughs.

“My María Alegre is without a doubt a loca,” she says, hugging me tight.

A Memory of María Alegre

Mami sits on the floor in the middle of María Alegre’s messy room. As long as she does not bring food in, María Alegre is allowed to turn her space into whatever she thinks of for the day. Under her bed there is a huge suitcase full of costumes. Mami never knows what María will become when she goes into her closet to dress up. Sometimes she is a ballerina, sometimes a clown, but she is always a dancer. María loves dancing and music. It is Mami’s job to choose the music for dancing.

“Ready?” María Alegre yells from under the sheet she has thrown over her head while she changes into a new costume. Mami gets up and stands close to the bed. Sometimes María Alegre will jump off the bed. She does not always land on her feet.

“I am ready, María Alegre,” Mami announces. A very fast mambo song blasts out of the speakers. María Alegre jumps into Mami’s arms, almost knocking her down. Then they begin to do the mambo. The mambo is a fast dance and you have to be able to move your shoulders, hips, and feet at the same time. Mami closes her eyes and tosses back her long, curly black hair. She takes her skirt in her hand and turns so fast that it fans out and María Alegre can feel the breeze and smell her special vanilla and cinnamon perfume. María Alegre tries to imitate Mami’s mambo style, but she gets tangled up in her long skirt and falls in a bundle to the floor, her toilet-paper breasts rolling out of her blouse. Mami picks her up laughing, and on her knees, she shows María Alegre how to swing, sway, shake her hips and shoulders, moving her feet only a tiny little bit. Mami is a great dancer — everyone says so. And whenever there is a party, people make a circle to watch her and Papi dance.

But it has been a long while since they have danced together. When he comes home from work these days, he does not want to go anywhere. They argue because he wants to live in the barrio, where he was born, again. She does not want to leave the job she loves. She keeps promising him that when María is older, they will go to America. She wants María to go to a good college. She teaches María perfect textbook English so that she will pass the exams. Mami corrects María’s pronunciation of hard English words that have sounds you do not hear in Spanish, like the th. “Thousand, not dousan, María. Put the tip of your tongue under your teeth and blow out a little air.” María goes around practicing her th sound, sounding like a leaky car tire: th, th, th, thousand.

Mami misses the parties and the dances she used to go to with Papi. But María Alegre keeps her in practice. In the last month or so, María Alegre has decided that one more thing she wants to be when she grows up is a professional dancer; although to be a teacher like Mami is also something she dreams about.

When the mambo ends, María Alegre yells out, “Now a bolero!” Mami puts on an old slow love ballad by Felipe Rodriguez and the sad violin music fills the room. The singer sounds like he is crying while singing this song about two people who love each other saying adiós, adiós. Mami and María Alegre hug-dance to it with María Alegre laying her head on Mami’s middle and holding her tight. Mami is short, only a foot and a half taller than María Alegre, who is tiny, so she puts her cheek down on María Alegre’s head. Finally when the song is over and Mami tells her that it is time for her to help clean their casita, María Alegre does not protest too much.

“So that Papi will see it nice when he comes home?”

“Yes, niña.” Mami has explained it all to María Alegre several times already, but she likes to hear things three or four times. It is not that she is slow — she just likes to memorize things. She can repeat almost anything you have ever said to her — word for word. It can get

very annoying sometimes. “Papi is coming home to stay, María Alegre. But I have to go pick him up tomorrow. I will be away three days. Your abuela will be here in the morning. You must be nice to her, and do your homework without being told.”

“Then you and Papi will come home in a new car.”

“Sí, María Alegre,” Mami says in a more businesslike voice. “Pero, now it is time to work.”

Flowering

The day came when I was no longer a child. By then I knew that la tristeza, Papi’s sadness, had become a part of our family. He only sang sad songs and never danced with Mami or me.

“He needs to go home,” Mami told me.

“He is home,” I argued.

But she was right. His feet wanted to walk on the concrete of the city where he had been born. He complained of the sand that burned his feet all day long on the beach that he cleaned for strangers. He said the sand was in his clothes, his eyes, his ears. The sand made his eyes water and tears run down his cheeks.

“Give me snow any day of the week,” he liked to say.

And Mami did. She gave him snow for Christmas of the year I turned fourteen. “Tickets to Kennedy, good any day of the week,” she said to him.

He carried the white envelope in his shirt pocket for weeks, like a small white flag of surrender. I knew he wanted us to go with him.

“I will not leave the Island,” my mother said.

“I cannot stay,” my father said.

María Triste had to decide between parents, languages, climates, futures.

“Hija, what do you want to do? Will you go to the mainland barrio or stay on the Island?” they each asked me.

I saw my mother growing stronger as she planted herself more and more firmly in her native soil, opening up like a hibiscus flower, feeding on sand and sun. I saw my father struggling against the imaginary sand that cut his skin, I heard him losing his voice — sand in his throat, sand in his lungs, he said.

“I will go with Papi. I will explore a new world, conquer English, become strong, grow through the concrete like a flower that has taken root under the sidewalk. I will grow strong, with or without the sun.”

El Súper and his daughter, we are famous to the tenants

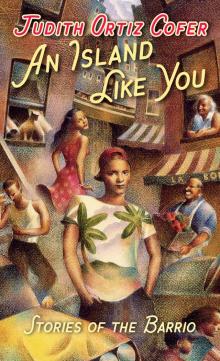

An Island Like You

An Island Like You Call Me Maria

Call Me Maria